Liquified Natural Gas in Oregon: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 21: | Line 21: | ||

Apparently the critics were right. | Apparently the critics were right. | ||

[http://www.oregonlive.com/business/index.ssf/2012/04/oregon_liquified_natural_gas_e.html Now Oregon LNG's plan has gone through a 180 degree change], reports The Oregonian. | [http://www.oregonlive.com/business/index.ssf/2012/04/oregon_liquified_natural_gas_e.html Now Oregon LNG's plan has gone through a 180 degree change], reports The Oregonian. Now the same backers are proposing a $6 billion gas export facility, not a gas import facility. | ||

[http://www.oregonlive.com/environment/index.ssf/2012/03/port_of_coos_bay_wants_to_flip.html Another LNG export proposal for Coos Bay] went though a similar flip-flop, from import to export. Other export terminals are proposed on the coast of British Columbia, as well as the Gulf Coast of the United States. The successful use of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques have flooded the domestic market with gas. | [http://www.oregonlive.com/environment/index.ssf/2012/03/port_of_coos_bay_wants_to_flip.html Another LNG export proposal for Coos Bay] went though a similar flip-flop, from import to export. Other export terminals are proposed on the coast of British Columbia, as well as the Gulf Coast of the United States. The successful use of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques have flooded the domestic market with gas. | ||

Revision as of 21:36, 19 April 2012

<< Back to: Green industry <<

Liquefied natural gas (LNG) is natural gas (predominantly methane) that has been converted temporarily to liquid form for ease of storage or transport. LNG takes up about 1/600th the volume of natural gas in the gaseous state. For ship transport, the gas is chilled to approximately negative 260 °F (127 °C), condensing the gas into a liquid, making it easier to ship.

At the terminal, the LNG gas is transformed from liquid to a gaseous state and transported in a gaseous form through pipelines.

Three Liquefied Natural Gas projects have been proposed in Oregon — Oregon LNG (near Astoria), Bradwood Landing (near Claskanie), and Jordan Cove (near Coos Bay). All three proposals for LNG terminals in Oregon planned originally to IMPORT natural gas (in the interest of national security). The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission would have to sign off on any terminal.

Today, everything has flipped. Now both the Astoria and Coos Bay natural gas terminal proposals plan to EXPORT natural gas, not IMPORT it.

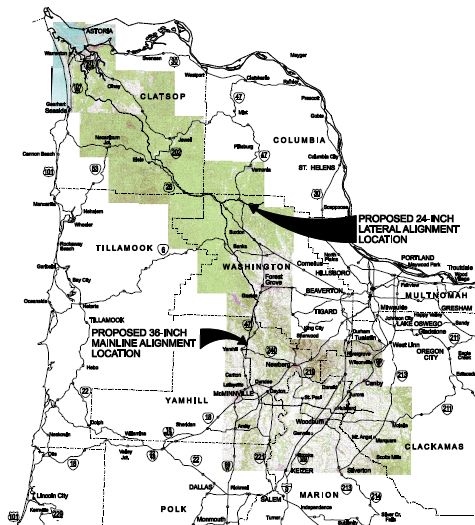

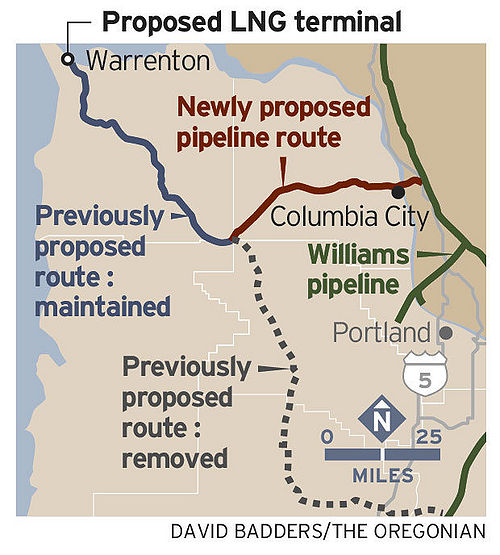

The Oregon LNG project, near Astoria, would include a marine receiving terminal, three full-containment 160,000 cubic meter LNG storage tanks, and facilities to support ship berthing and cargo offloading. The proposed Oregon LNG receiving facility in Warrenton, Oregon, would be eight miles (13 km) west of Astoria, Oregon, on the Columbia River. The terminal originally planned to receive Liquefied natural gas shipped from overseas then transported down state through a new pipeline with a route similar to the competing Palomar Pipeline.

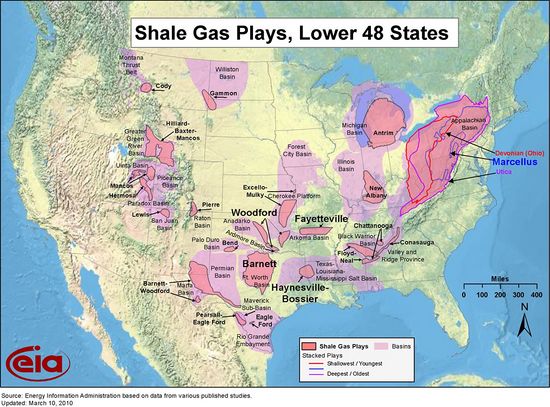

Oregon LNG battled Clatsop County officials over its right to build the pipeline that would bring in gas from the ships and move it to California. Skeptics say the entire economic rationale for importing natural gas to the United States has become questionable given the huge new reserves of shale gas in the United States and Canada. Gasland, a documentary by Josh Fox, explored environmental impact of hydraulic fracturing used to extract the gas.

Apparently the critics were right.

Now Oregon LNG's plan has gone through a 180 degree change, reports The Oregonian. Now the same backers are proposing a $6 billion gas export facility, not a gas import facility.

Another LNG export proposal for Coos Bay went though a similar flip-flop, from import to export. Other export terminals are proposed on the coast of British Columbia, as well as the Gulf Coast of the United States. The successful use of hydraulic fracturing and horizontal drilling techniques have flooded the domestic market with gas.

Oregon LNGsays export economics from Oregon stack up well against Gulf Coast competitors. Oregon LNG is also proposing a different route for the pipeline.

"LNG import was really unpopular in Clatsop County, and LNG export is going to be wildly unpopular in Clatsop County," said Dan Serres, an organizer with the conservation group Columbia Riverkeeper. Both Oregon LNG and the Jordan Cove LNG proposal in Coos Bay are at the start of a long permitting odyssey.

The Bradwood Landing LNG import terminal, upriver near Claskanie, was apparently stopped in March of 2011, when a 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals decision threw out the license for the Bradwood Landing terminal.

According to Columbia Riverkeeper Executive Director Brett VandenHeuvel, "Bradwood LNG was a dominant environmental issue for five years and now it is officially over." Foes feared possible impacts on fish, forests and farms.

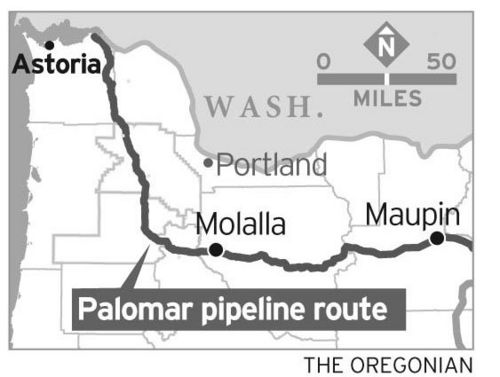

The NorthernStar Natural Gas company planned the Palomar Pipeline, feeding the Bradford landing export facility, upriver from Astoria. It was planned to be a joint venture between NW Natural and Calgary, Alberta-based TransCanada Corp to import Liquified Natural Gas. A planned 36-inch diameter pipeline would stretch 217 miles from TransCanada’s Gas Transmission Northwest Pipeline in central Oregon to a point on the Columbia River near Astoria where it was to connect the Bradwood Landing project.

The Jordan Cove LNG storage facility would be located within the Port of Coos Bay, approximately 7 nautical miles from the entrance of the navigation channel, and pipe it south to California. Oregon's Land Use Board of Appeals has kicked back Coos County's approval of the Pacific Connector Gas Pipeline, ordering the county to reconsider the project's impact on the Olympia Oyster.

The 234-mile pipeline would carry gas from the proposed Jordan Cove liquefied natural gas terminal in Coos Bay to an interstate gas hub in Malin, near the California border in Central Oregon. From there, the gas would head south to California.

The Port of Coos Bay now wants to flip from importing to exporting liquefied natural gas, reports the Oregonian. Backers of the controversial Jordan Cove Energy Project are starting their regulatory odyssey anew, filing paperwork in Februrary, 2012 with the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission. Jordan Cove and the associated Pacific Connector pipeline originally won federal approval in December 2009, only to become ensnared in state and local permitting issues.

Oregon Senators Ron Wyden and Jeff Merkley have both expressed reservations about gas exports because of likely impacts on domestic prices. Even LNG proponents concede that gas exports are likely to raise prices. And Rep. Peter DeFazio recently authored a bill that would prohibit the use eminent domain to build a pipeline if that pipe is used to export LNG, reports The Oregonian.

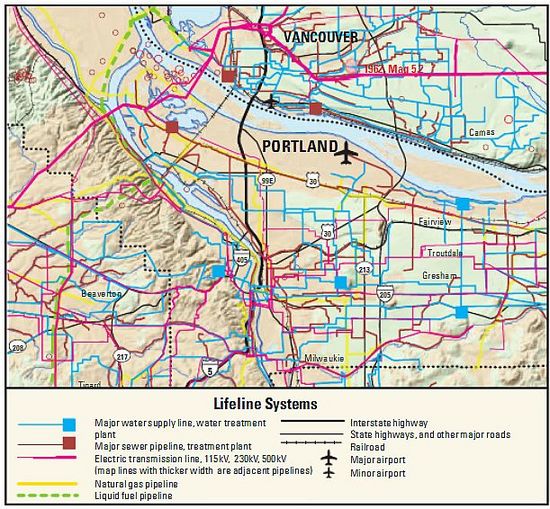

Oregon Geology maps out Portland's lifeline systems and Tsunami Hazard zones.

Natural gas is trapped within shale formations. The combination of horizontal drilling and hydraulic fracturing has made large volumes of shale gas available for the first time and rejuvenated the natural gas industry in the United States. Shale gas resource and production estimates increased significantly between the 2010 and 2011 and are likely to increase further in the future.

NEXT: Bio Mass in Oregon

Back to: Green industry <<